Baffinland Iron Mines’ proposed expansion of its Mary River iron ore operation on the northern tip of Baffin Island, in Canada’s territory of Nunavut, has suffered a major blow after a review board advised against the project on environmental grounds.

After four years of consultations and deliberations, the Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB) rejected last week the miner’s request to more than double output to 12 million tonnes a year, eventually reaching 30 million tonnes annually.

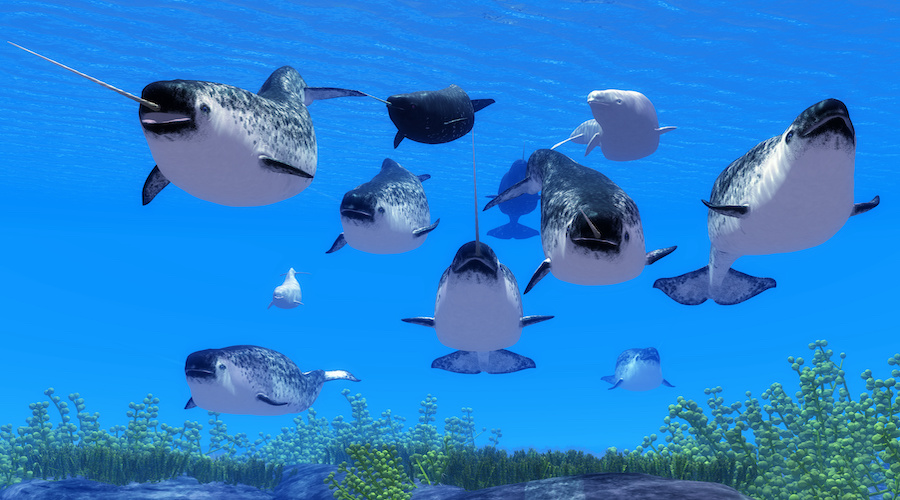

The board cited “significant adverse ecosystemic effects” on marine mammals such as narwhals, fish, caribou and other wildlife, which in turn could harm Inuit culture, as the main reason for the decision.

The company said it was both surprised and disappointed by the board’s decision.

“Our … proposal is based on years of in-depth study and detailed scientific analysis, and has considerable local support based on years of consultation with Inuit and local communities,” chief executive officer Brian Penney said in the statement.

“We will be asking the federal government to consider all of the evidence and input and to approve the … application with fair and reasonable conditions,” Penney noted.

Dan Vandal, the federal northern affairs minister, has 90 days to either side with the review board or the mining company, in which steel giant ArcelorMittal has a 28% stake. The rest of Baffinland is held by Nunavut Iron Ore Inc., which is controlled by a Texas-based private equity firm called the Energy & Minerals Group.

Mary River, considered one of the world’s richest iron deposits, opened in 2015 and ships about six million tonnes of ore a year.

If the expansion is approved, Baffinland would send about 12 million tonnes of the 30 million tonnes via the North Railway to Milne Port. It also plans to build a second railway to Steensby Port, from which it intendes to ship an additional 18 million tonnes of ore a year.

Current shipping volumes have already had a “devastating” impact on the area’s narwhal population, the world’s densest, vice-chairperson of the Mittimatalik Hunters and Trappers Organization, Enookie Inuarak, said in an emailed statement.

Narwhals are a type of whale with a long, spear-like tusk that protrudes from its head. The marine mammal is an important predator in Eclipse Sound and other Arctic waters, as well a major food source for Inuit in the region.

Last year, a group of hunters from Arctic Bay and Pond Inlet blocked access to the mine in protest for the company’s ice breaking practices due to their negative impacts on narwhals.

The company agreed to avoid ice breaking in spring, based on “the precautionary principle that is the foundation of our adaptive management plan,” Baffinland’s CEO said in a statement at the time.

Loss of economic benefits

In its report, the NIRB acknowledged the loss of economic benefits Phase 2 would cause to Inuits, which has been conservatively estimated at C$2.4 billion (about $1.9bn) based on the current size of the known mineral resource.

“Many residents in the affected communities also expressed the view that the potential positive socio-economic benefits of the proposal focus on financial benefits, while the negative socio-economic effects focus on effects on land use, harvesting, culture and food security that cannot be compensated with money,” NIRB said in the 441-page report.

The same board recommended against construction of the Back River gold in Nunavut’s Kitikmeot region in 2016. Then-federal minister Carolyn Bennett rejected that advice and asked NIRB to give Sabina Gold & Silver’s (TSX: SBB) project a second chance.

The mine was approved the following year and the project stands as a fully permitted, financing package settled and shovel ready mine.